Modernity needs a crucible and a tree, the former where seminal ideas and practices germinate and the latter where they flower. If there was one crucible of art in India in the 19th century, it was Calcutta. Calcutta could be looked upon as a crucible of modernity, where over the past centuries, it has been a melting pot for various currents. They were ignited by economic, social, and cultural transformative forces that shaped the urbanisation of Calcutta. In the popular and intellectual terms of discourse, modernity implies the production and adoption of new ideas and ways of thinking that defy or depart from the traditional lifestyle and ideas. In this sense, modernity reinvents itself and changes its shape with every stage in the socio-economic transformation of society, and can therefore be ancient and contemporary. Modernity in Calcutta introduced the concepts of freedom, equality, and fraternity, which helped frame democratic and egalitarian forms of political governance in the modern Western world in the 19th and 20th centuries. This was also felt in Calcutta.

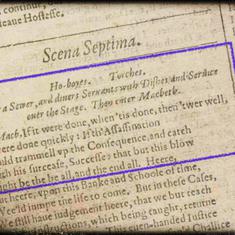

Calcutta in the 19th century became the locus of exchange between the British metropolis and its Indian colony. Its port, built by the British, served to export native raw materials to England to grease its industrial wheels. It also served to import Danish Christian preachers who set up the first printing press in Srirampore, near Calcutta. It also brought an Englishman named David Hare to Calcutta, where he opened a school to teach English to Bengali students.

The Hindoo College set up in 1819, employed a brilliant young teacher, Henry Derozio (son of a Portuguese father and an English mother, who was born in Calcutta). He imparted the ideas and thoughts of contemporary Western philosophy and political science to his Bengali students. Thus a new generation of Bengali intelligentsia was produced which approximated to the role of modernity, by both interrogating the sanctity of their past indigenous tradition, as well as challenging the authority of the current colonial order.

One of the students of Hindoo College, Kishorichand Mitra was to describe the spirit of modernity of those days in the following memorable words:

The youthful band of reformers who had been educated at the Hindoo College, like the tops of Kanchanjunga were the first to catch and reflect the dawn.

These students, along with leading intellectuals and social reformers like Rammohan Roy, Radhakanta Deb, Dwarkanath Tagore, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, as well as business entrepreneurs like Ramdulal Dey and Motilal Sheet, played a pivotal role in introducing the ideas of a cosmopolitan modernity, and encouraging practices in society and culture in conformity with that contemporary global concept of modernity. Calcutta subverted the concept of colonial modernity that was sought to be imposed by the British rulers. By using the same tools of knowledge that were given to them by these rulers, they constructed a different concept of modernity.

The British rulers wanted to mould a generation of Bengalis, a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect. They groomed this class in the hierarchal order of barristers, civil servants, and army personnel to be trained in Britain, followed by the next subordinate group of Bengalis, who were trained in Calcutta to operate as teachers, lawyers, medical practitioners, and junior employees in the administration, as deputy magistrates and clerks, to serve their British bosses.

But such transactions between the rulers and the ruled in colonial Calcutta led to a new conceptualisation of modernity by these Bengali middle classes. Modernity was no longer a monopoly of Western colonial powers. Many among the Bengalis who were trained in Lincoln’s Inn as barristers, or as civil servants in London, came back to Calcutta with ideas of modernity to which they had been exposed during their stay abroad, ideas of democracy, parliamentary elections, judicial independence, accountability by the rulers, local selfgovernance, and right to self-determination. They began to assert their rights as Indian citizens on these lines, some within the colonial order, some daring to break out from it.

It is in Bengali culture that Calcutta has played a major role in introducing modernity. The term modernity here suggests the ability of indigenous litterateurs and artistes to respond to extraneous new thoughts and styles and techniques, and reinterpret and use them in their own creative ways. From the nineteenth century onward to today, Calcutta has remained a crucible, where the exciting encounter between local and traditional Bengali ideas and forms, and their counterparts from the West, has led to a succession of creative output in literature and the arts.

We are familiar with the rise of the Bengali novel with Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, the multi-faceted contributions of Rabindranath Tagore to modern Bengali culture, the founding of the Bengal School of Art under the auspices of Abanindranath Tagore, and still later the Calcutta Group of painters like Rathin Maitra, Gopal Ghose, Paritosh Sen. But, it is important to note in this context that it was not only these members of the educated middle classes, who participated in this encounter between the East and the West. Calcutta’s lower orders created a distinct culture of their own in the nineteenth century by adopting the technology of contemporary modernity, and interpreting the new ideas of modernity in their own way. We thus find urban folk singers, like kobiwalas, panchali-singers, and jatra actors, learning to use newly introduced musical instruments, like the violin, harmonium, and clarinet, to sing songs that lampooned the manners and habits of the westernized Bengali babus who imported these same instruments to Calcutta.

We find traditional scroll painters coming to Calcutta and discovering the importance of paper, which was easily available due to the setting up of paper manufacturing mills by British entrepreneurs. They began to use paper to paint both the traditional religious themes, and also to depict the new urban environment. They came to be known as Kalighat pats, since these painters settled down near the Kalighat temple in Calcutta.

Jamini Roy was the urban patua who built a bridge to modernity with his iconic painting. Similarly, poets and writers from the lower orders in nineteenth-century Calcutta made use of another form of modernity, the newly introduced printing press. Some among them set up printing presses in the Battala area of north Calcutta, which opened up a wide avenue for the publication and distribution of popular literature, and also woodcuts.

Excerpted with permission from ‘A Crucible and a Tree’ by Alok Bhalla, Sumanta Banerjee, and Manjiri Thakoor in Modernity in Indian Art: Reflections, edited by Harsha V Dehejia, Aleph Book Company.