In the context of any possession ritual (not limited solely to serpent worship, but including practices like kola or theyyam), the process of spirit possession may be seen as a manifestation of an altered state of consciousness or trance. This ethereal state is often induced through rhythmic movements, musical cadences, meditative practices or hypnotic techniques, which are known to produce distinct alterations in perception, cognition, and behaviour.

When dancers engage in repetitive movements like spinning, swaying or shaking, it induces physical fatigue. This combination of physical exertion, rhythmic motion and sensory stimulation – enhanced by music and the fervour of the crowd – can transform the medium’s state of consciousness, allowing them to become possessed by the spirits believed to inhabit sacred realms. Psychologically, this transformation might be seen as a form of dissociation or absorption. The cultural and religious context of the dance ritual plays a crucial role in shaping how the medium experiences and interprets spirit possession.

Among the older generations, it is widely believed that when a dancer reaches this state, they may be capable of delivering oracular prophecies, perceiving the past or future, or communing with divine entities. We have seen such practices in the Daivaradhane rituals of Tulunadu and in Kerala’s Theyyam and Velichapaadu. Similar oracular activities are part of other dance rituals like Naagamandala, Kaadyanaatta, Thullal and Jaagar, making these events not just performances but vital moments of divine communication for the community.

Let us now explore some specific examples of these powerful serpent possession dances across different states.

Dakkebali, Naagamandala, Kaadyanaatta

In Dakkebali, the naagapatri – a priest from a special lineage of the Shivalli brahmin community – represents naagabrahma, while a male from the Vaidya community becomes the naagakannike, which is likely a variation of the term naagakanyaka. Together, they embody the male and female aspects of the Naaga deities. The Vaidya, skilled in playing the small drum called dakke, sings along with the dance, while the paatri gets possessed. The devotees watch in awe as this powerful and sacred performance unfolds.

The devotion, however, is not confined to simple offerings; on special occasions, it culminates in elaborate rituals such as Naagamandala, where the faithful gather with hearts full of prayers.

Some seek to break the serpent’s curse (dosha), while others pray for blessings or the prosperity of their community.

For this sacred dance, a pandal or tent is erected before the shrine, and an intricate mandala is created on the ground. The mandala – reminiscent of the sarpakalam in Kerala – is drawn using powders made from natural elements – crushed leaves, saffron, turmeric and rice powder. At its centre is a serpentine figure, coiled in hypnotic patterns, each curve a testament to a larger cosmic order.

The serpent, depicted with three, five or seven hoods, stretches within a circle ten to fifteen feet wide, depending on the occasion’s grandeur. A full mandala, with its sixteen knots, mirrors the pinnacle of cosmic design – a mathematical precision that reflects the serpentine order. Viewed from a distance, the mandala stirs awe, offering a glimpse into the hidden world of serpents. Above this artwork rises a fragile yet sacred structure adorned with areca flowers, symbols of purity and blessing.

As the night deepens, the paatri, wild and untamed, his hair loose, holds a bunch of areca flowers, their tender florets sticking to his face, giving him a surreal, otherworldly appearance. Dressed in a dhoti, he becomes both human and spirit, blurring the boundaries between the mortal and the divine. His counterpart, the naagakannike, dressed in half-male, half-female attire, embodies the androgynous nature of serpentine divinity.

As the dance progresses, the paatri moves like a serpent – his body sinuous, fierce and unpredictable. The naagakannike provokes him further, as they dance, knotting and unknotting the lines of the mandala. Their interaction is a delicate balance of reverence and challenge. The crushed areca flowers stick to his body, as if he is moment by moment transforming into the serpent spirit itself. The air fills with the rhythm of drums, cymbals and the scent of flowers, creating a terrifying yet beautiful spectacle – a dance that evokes both fear and devotion.

As the night wears on, the paatri’s movements become more serpentine, mimicking a cobra coiling around its prey, while the naagakannike sings praises to the serpent deity. In the final act, the serpent spirit is both enraged and appeased, moving from wrath to grace. The ritual’s climax, the “tying and untying of knots”, reflects the duality of life – chaos and order, anger and peace, human and divine.

While Naagamandala and Dakkebali hold a revered place in the mainstream religious practices of Tulunadu, a lesser-known, yet equally profound, serpent ritual exists among the Dalit communities of Karnataka. This ancient dance, known as Kaadyanaatta, draws its name from the word Kaadya, meaning the black king cobra, maybe an echo of the legendary Kaaliya Naaga. The shrines of Kaadya are hidden deep within the forests, far from the sanctuaries of more widely recognised traditions. These forest shrines stand as silent guardians of the past, centred on an anthill, where stones representing serpents lie scattered. Surrounding the anthill are hundreds of clay pots, each marked with serpent hoods, varying in number from one to eleven. Each clay pot bears the weight of generations of belief.

The veneration of clay pots is observed in other parts of the country, notably with deities like Manasa (in Bengal) worshipped as a clay pot known as Manasa-ghata (or “ghot” locally). The pot likely symbolises the womb, suggesting a connection to fertility rituals, according to scholars. Even in rural Maharashtra, live cobras are kept in earthen pots for reverence. The link between snakes and pots is intuitive – snakes may have been captured and kept in pots, and Tamil beliefs hold that snakes are drawn to pots in summer for their coolness. This association could tie into ancient beliefs about pots containing poison or soma, the puranic elixir.

Sarpam Thullal

As we move further down towards Kerala, the connection to serpents – both physical and divine – runs through rituals like Sarpam Pattu, Sarpabali and Thullal, where intricate floor patterns, known as Kalams, are drawn using coloured rice powder, charcoal and coconut shells. These serpentine drawings, crafted with artistic precision, are believed to invoke the presence of the serpent deities. Women play a central role in these rituals.

In Thullal, a booth or “pandal” is erected, covered with a silk or cotton canopy. On the floor, a large snake figure is created using five-coloured powders, and rice is scattered. Incense is burned, and a lamp is placed on a plate as offerings to the snake deity. The male from the Pulluvan community and his wife begin their music, with the wife keeping time by striking a metal vessel. As their songs in honour of the serpent deity rise, young women following ritual baths begin to sway and quiver in time with the music. Their hair is let loose, and in their heightened state of excitement, they beat upon the floor and rub out the snake figure using palm flowers. After this, they proceed to a nearby snake grove, prostrate themselves before the stone snake idols, and regain consciousness. They are offered milk, tender coconut water and plantains as part of the ritual.

The ceremony is believed to reflect the approval or displeasure of the serpent gods. If the gods do not manifest through one of the participants, the ceremony is extended until they are properly propitiated. Sometimes, the snake figure may need to be destroyed and redrawn many times, stretching the ritual over several weeks. Each time the figure is wiped away, men with torches dance in step with the Pulluvan’s music. As a permanent mark of devotion, the family may eventually erect a small platform or shrine, where they continue their worship annually.

Jaagar

In the hills of Uttarakhand, as briefly mentioned in the previous chapter, the concept of Jaagar is deeply woven into the fabric of local traditions. This ancient form of Indian folklore has coexisted with traditional Hinduism for centuries, serving as a unique bridge between the spiritual world and the mortal realm. Jaagar, meaning “awakening” in Hindi, is a ceremonial practice meant to awaken the supernatural powers of Puranic gods (devas), folk gods (devatas), or even spirits of the deceased (bhutas). The definition may vary but the ritual, led by a storyteller called the Jagariya, involves invoking these supernatural entities through chants, mantras and ballads, all while accompanied by the rhythmic sounds of instruments like the daunr and thali.

This practice bears a strong resemblance to the paardanas of Tulunadu, particularly in the kola tradition, where ancestral spirits are invoked with song and dance. In both traditions, there is a sacred interaction between the spirit deity and the human, with the chosen Jagariya acting as a vessel for the local deities.

In the case of the Jaagar dedicated to the Naagadevatas or Naagaraaja, the serpent deities, the person selected as the vessel experiences possession, as the deity takes over their physical form. This phenomenon often extends beyond the chosen individual, as others in the gathering may also become possessed, swept up in a frenzy of devotion and ecstasy, dancing wildly in a spiritual communion with the divine. The entire event becomes a powerful, otherworldly experience, where the boundaries between the physical and spiritual worlds blur, and the deities make their presence known through the human form.

These dance rituals, filled with vivid imagery, dynamic movement, and stirring music, leave a lasting impact on those who witness them. They are not simply performances; they are living expressions of an enduring connection between art, religion and the human spirit. Through these sacred acts, we catch a glimpse of humanity’s primordial desire to connect with the divine, a bond that has persisted through the ages. In the cases presented in this chapter, the connection is with the serpentine spirit of Naagadevatas. Such rituals are also part of folk traditions of Himachal and Assam as well.

These shared rituals – spanning different parts of the country – reveal common threads in the worship of serpent deities. It makes me wonder what ancient cultural exchanges may have flourished between these regions, or what has been lost over time in the relentless march of history. This deep connection between ritual, belief and the natural world finds its most tangible expression in the sacred serpent groves, which we will explore next.

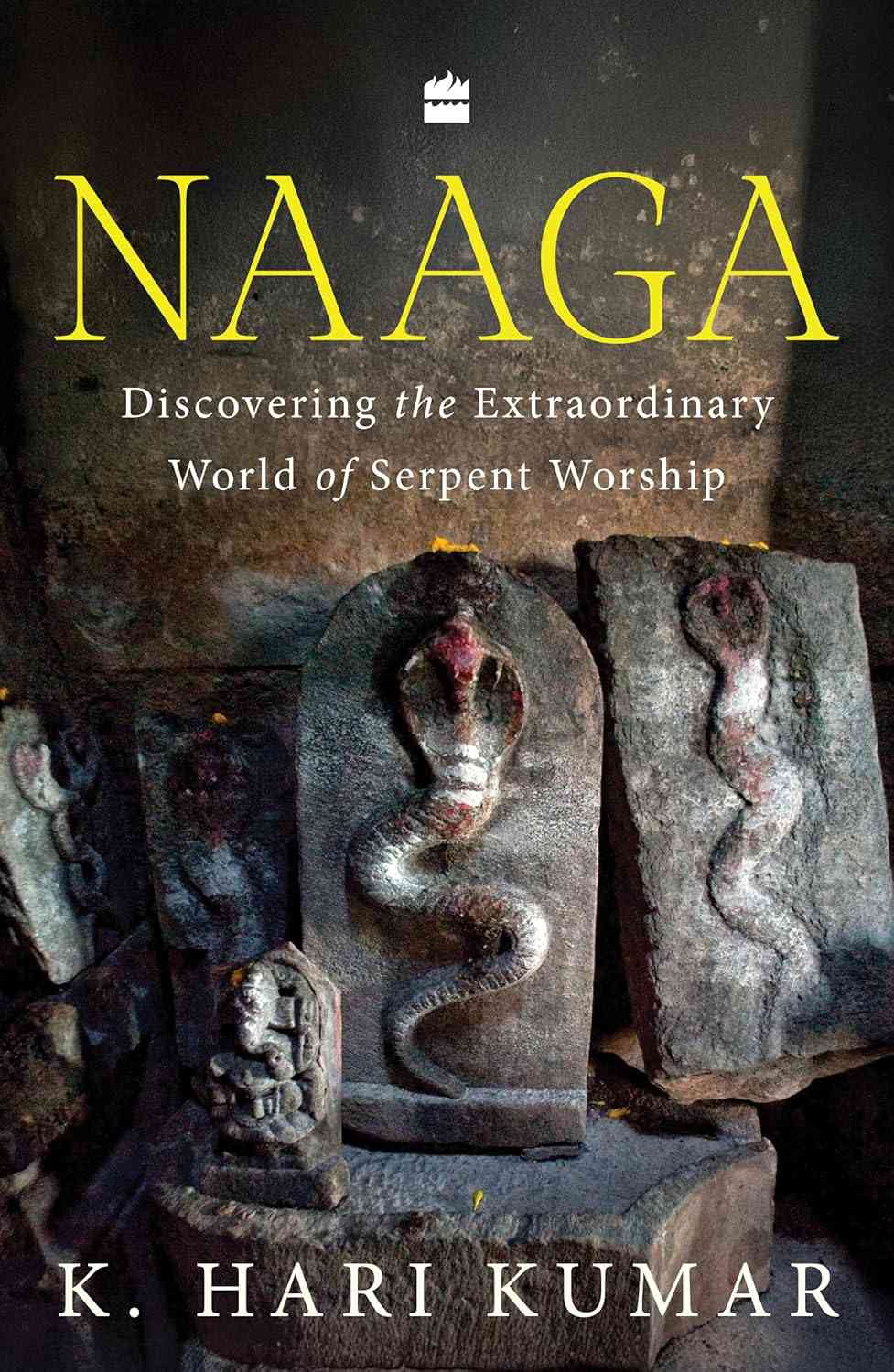

Excerpted with permission from Naaga: Discovering the Extraordinary World of Serpent Worship, K Hari Kumar, HarperCollins India.